Intro to CLI

Intro to CLI

Note: this assumes that you are working on a Mac OS or with Git Bash on a Windows machine.

- First rule of programming - try to think through what’s going on.

- Second rule of programming - ask questions when you don’t understand.

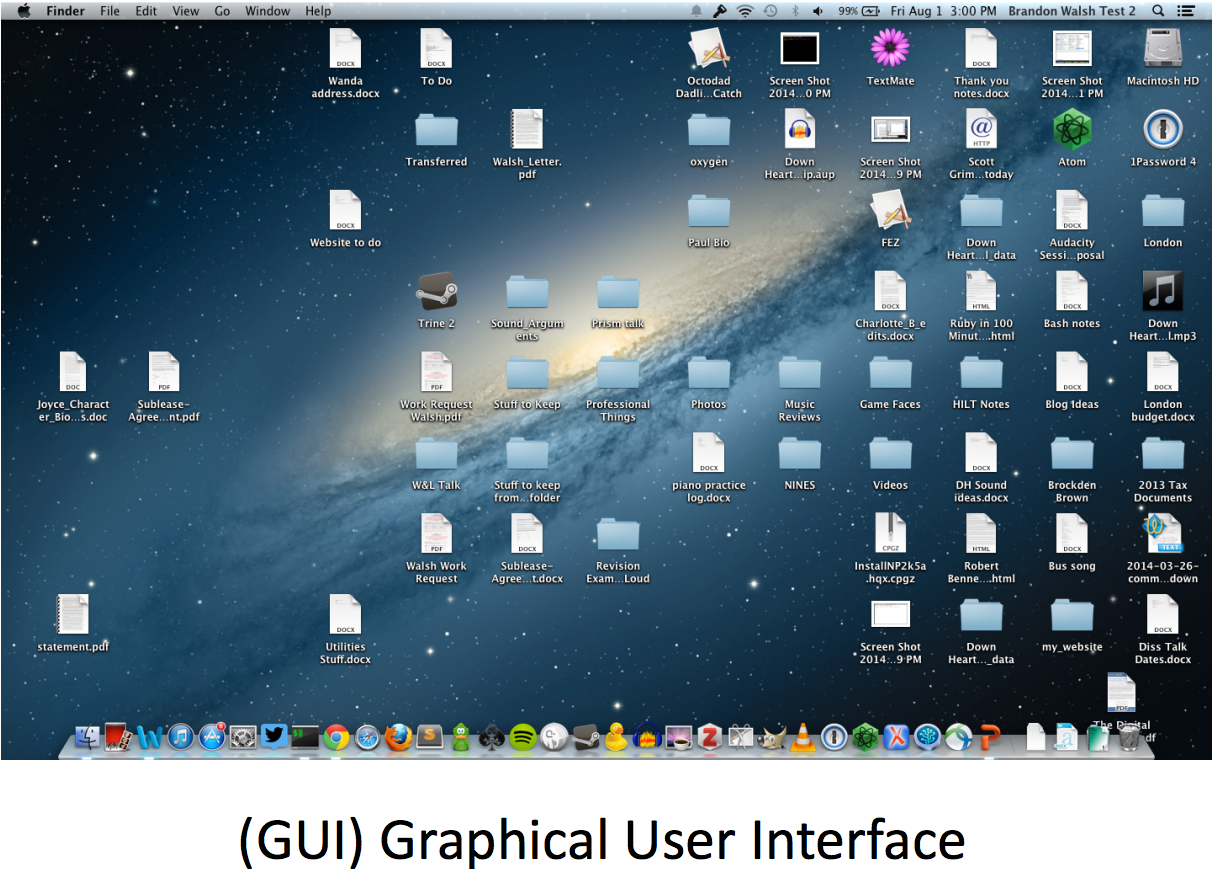

There are two ways of interacting with the computer. One is what we’re used to doing - we take a mouse and click around. It’s primarily image based. It’s called the Graphical User Interface or GUI. The GUI is based around images and interacting with them.

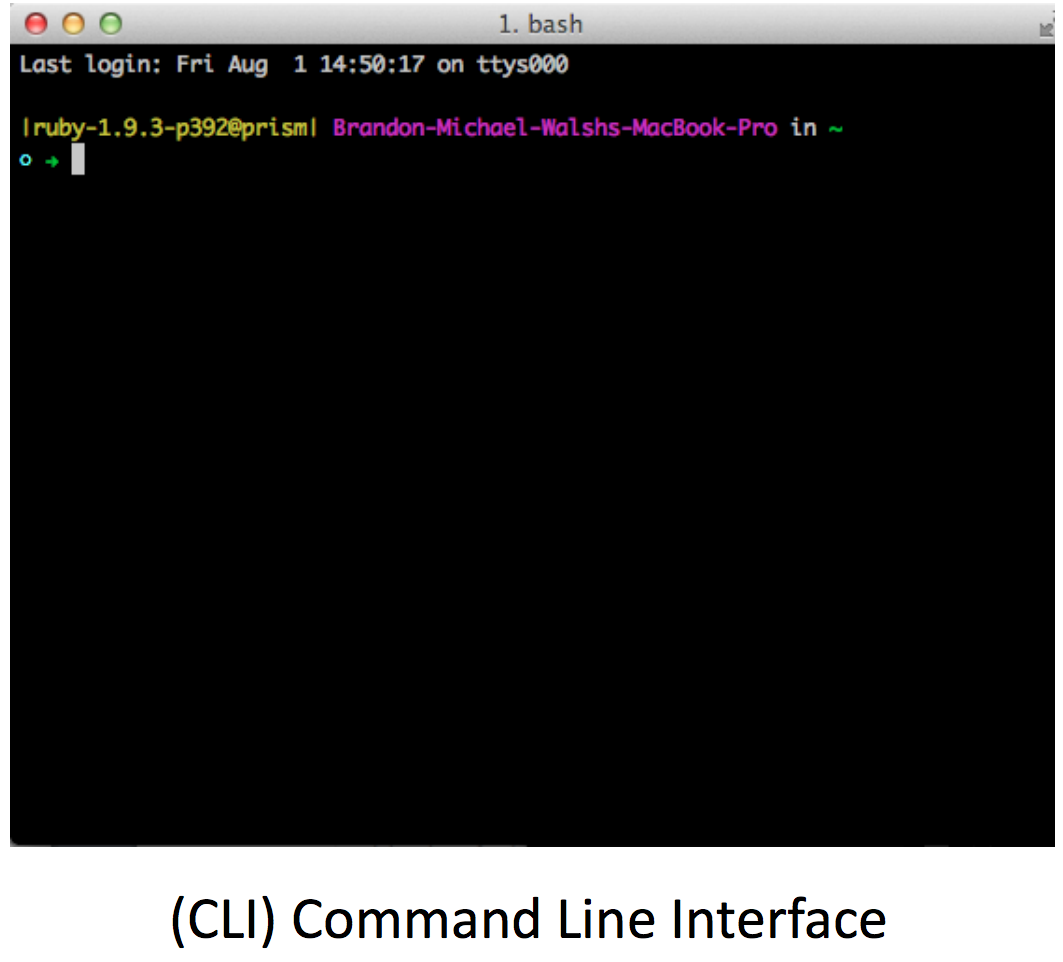

But there’s a much older way that uses only text to interact with the computer. Search (go up to the magnifying glass in the upper right corner) for “terminal.” Even if you don’t think you have it, you do. It ships on all Mac computers, at least. Windows will be different.

You should get something looking like this –

You’ll see a window with a prompt for you to enter commands. Accordingly, we call this a command prompt or the command line. You might see something similar in any movie that has someone hacking away at a computer as a timer runs down.

The lesson today is that anything you do by clicking around on the computer can also be done on the command line. In fact, you can do way way more on the command line. The GUI has to simplify things in order to make them intuitive. But the command line strips all the bells and whistles away and gives you the raw power of interacting with the computer directly. Think of it like driving stick for the first time. It can feel complicated and alienating. Once you get the hang of it, though, you will be able to take control of your computer in new and fantastic ways, and the command line forms the basis for pretty much everything we will do as digital humanists.

And it also feels fun. You’re a hacker! Woo hoo!

My terminal looks a tad different from yours because I’ve customized it to give me more information. It’s a little easier to look at, it tells me what folder I’m in, etc.

Here is how it works. You’ll be typing things in using this format. You tell the computer what to do and how to do it. Don’t worry about the dollar sign here – that’s just one of the ways that documentation tells us what to type in the terminal as opposed to what is part of the narrative of the guide. So if you see a dollar sign, you only type what is after that dollar sign into the terminal.

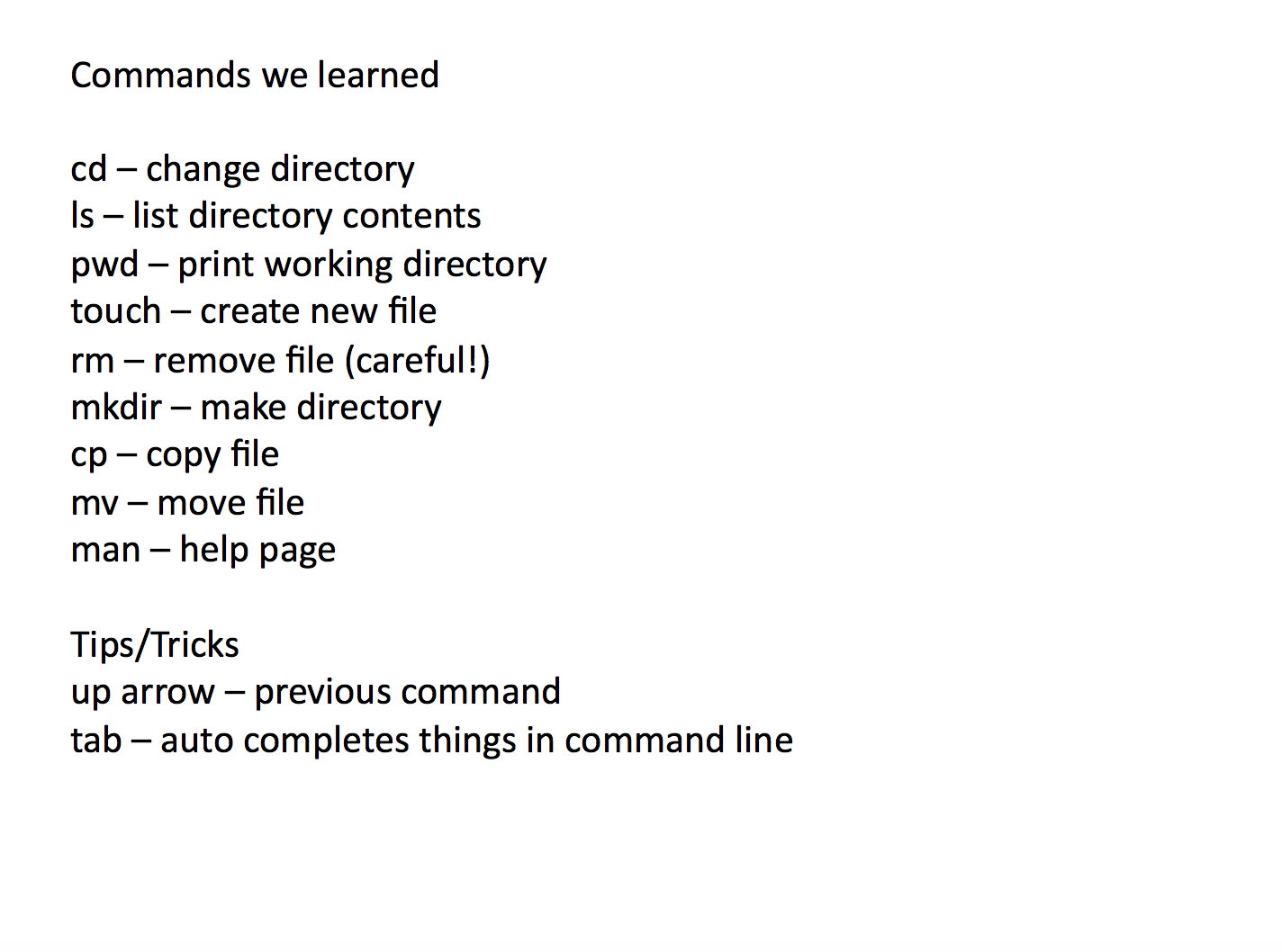

Here are the commands you’ll be using today. You can do LOTS with just this short list. We’ll learn through repetition.

Now switch to terminal. In general, the terminal works like this:

- You type a command in.

- The terminal attempts to run that command.

- More often than not, the terminal gives you feedback on how things went.

This feedback can be incredibly useful. A lot of times we can solve problems just by reading the terminal’s output.

The first and most obvious difficulty with the terminal is that, without pictures, it can be difficult to know where you are. So our first and most important commands relate to navigating around the computer. Where are we?

$ pwdMost of the terminal commands have somewhat intuitive relationships with what they do. pwd stands for “print working directory.” Directories are another name for folders. So if you type it, it tells you that we’re in the folder for your user name. OK, but what is inside that folder?

$ lsls lists the files in your current directory. In the users folder, you should see things that look familiar - applications, movies, pictures, etc. Just for the sake of giving you something you will recognize, let’s move into the folder that looks the most familiar - Desktop.

$cd Desktopcd stands for change directory. We have to tell the computer what directory to move into, and we give it Desktop. Note that the terminal, like virtually all programming, is case sensitive. ls again.

$ lsYou should recognize these things. We’re now seeing the contents of your desktop, both in the GUI and in the terminal. This will be handy, because you can see the magic happening in the GUI as you perform it in the terminal.

$ mkdir test_folderAnyone guess what mkdir does? Yep. Make directory. Spaces get whacky in programming (best to avoid them at this point), so get used to typing underscores. Take a look at the GUI. You should see a folder appearing in the GUI. MAGIC. Let’s also make sure that the folder appeared in the terminal.

$ lsGreat. It’s there. Now let’s change into it, just like we changed into the Desktop folder earlier. How would we do that?

$ cd test_folderBingo bango. Also, note that if you type part of the name of the folder and hit tab, it will auto-complete. The lesson for the week is that programmers are lazy. In general, I usually do a suite of commands when I move around to make sure I know what’s going on.

$ pwd

$ lsThis will tell you where you are and what is in your folder. There’s nothing in the folder right now. Let’s change that.

$ touch file.txt

$ lsWhat did we do? We made a file. Make sure that it’s there.

One thing I glossed over a moment ago - type pwd again. When you’re looking at the GUI, the graphic representation of your computer, you can see and interact with several different places at once. A single terminal window can only be in one directory at a time, but these directories are nested in one another. The test_folder directory is in the Desktop directory, which is in my user director. A simplified way of describing this relationship is called the “path,” the route that the computer would follow to find the folder that you want. pwd gives the file’s path. So this file’s path is:

Users/bmw9t2/Desktop/test_folder/my_file.txt

$ cd ..

$ pwdThe .. command joined with cd takes us up one directory, out of our current folder and into the directory which contains it. It’s a handy way for moving around.

Now is a good point at which to pause. Try moving around your computer using those commands - cd, ls, pwd. Move around a dozen or so times. You’ve got to just get these things under your fingers. Also a fine time to answer questions if anyone has them.

So we know how to create files. We’ll be doing PLENTY of editing them later on. For now, let’s clean up what we’ve done so far. We created a folder. But, godlike and drunk on our power, we can both create code and take it away.

$ rm file.txtAny idea what this will do? Remove file. Exactly. Check that it worked. If it didn’t, you might not be in the right folder. You have to be in the directory containing the thing you want to modify. You can also give the command line a path a la $ rm test_folder/my_file.txt

Before we finish up, there is an important last lesson. Make three files with any names.

$ touch magic_one.txt

$ touch magic_two.txt

$ touch magic_three.txt

$ lsA good tip here: if you press up in the terminal it reloads your most recent command. So you can easily modify your previous command if you want to, say, change the file name.

Another way you could do is the command cp (copy). You have to specify first the name of the file to be copied and then the names of the new files.

$ cp magic_one.txt magic_two.txtWe want to clean up our workspace and delete this whole directory. Let’s go back to the desktop to do so.

$ ..

$ rm test_folderThat’s the right command, but why didn’t it work? It is warning us that there are many files inside the directory so that we don’t accidentally delete a bunch of things. Fortunately, we can hit the computer with a hammer and force it to do our bidding.

$ rm -rf test_folder-r and -f are options. We combine them to tell the computer more information about what we want it to do. In this case, we are saying go recursively through and delete all the files in this folder.

The final lesson, then, is that with great power comes great responsibility. You could easily delete everything on your computer with a command like this deployed in the wrong way, so always make sure you know what you’re doing (do research online) before you type anything in.

The world is your oyster. So make sure you don’t explode the oyster.

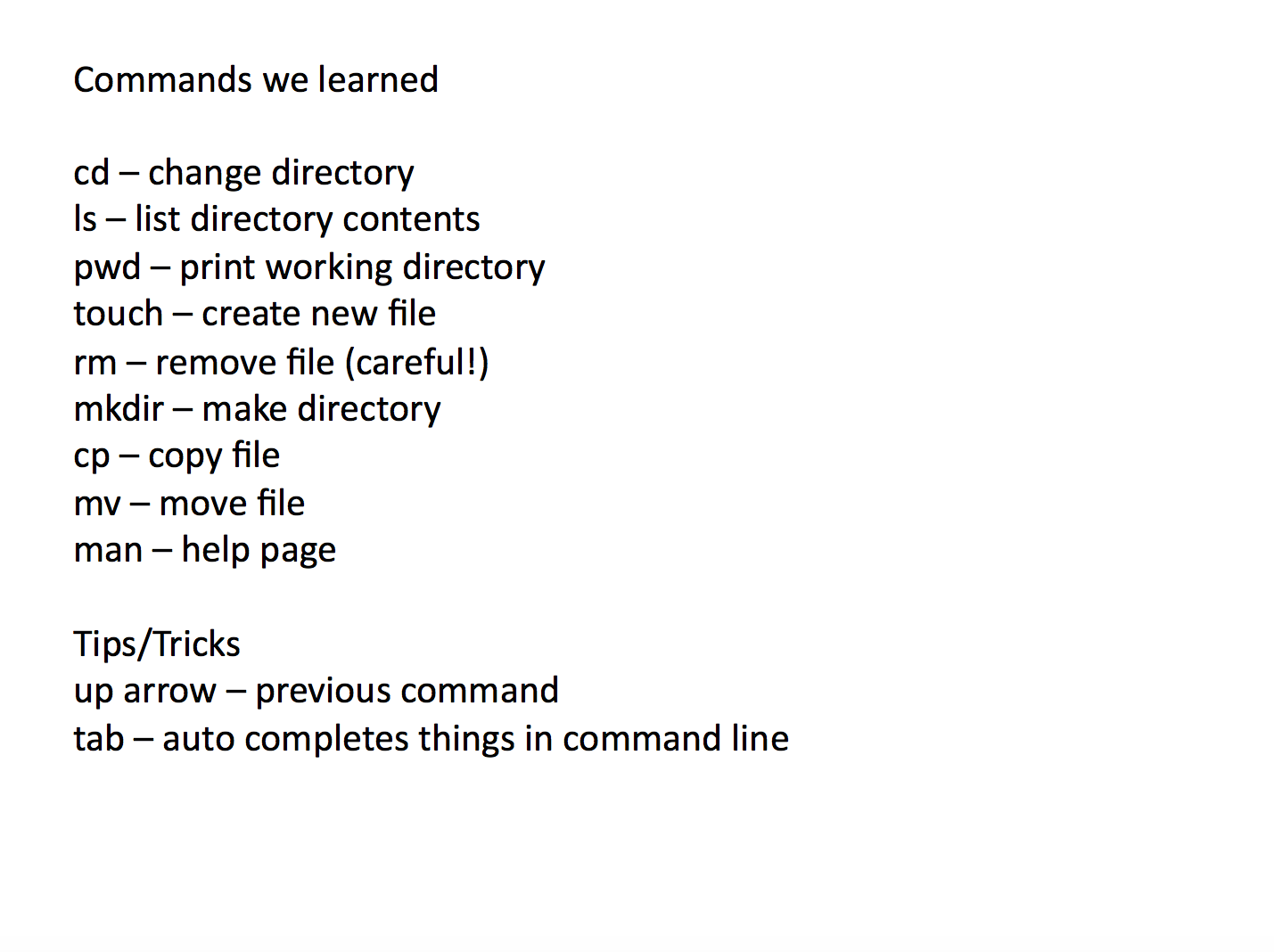

Cheatsheet for commands covered here